Tracked Eyes on Street

Use Mobile Eye-tracking Technology in Understanding Human Experience in Urban Environment

As eye-tracking studies show associations between human perception and cognitive processing, we start to bridge the gap of understanding what people see to how people see. However, challenges arise in a realistic environment. In most cases, people walking on a street are exposed to multiple environmental factors that are difficult to understand the causality of perception-action conceptually. Therefore, how actual environmental factors influence human urban interactions is still unknown or never seems to be fully understood.

This project proposes to leverage mobile eyetracking glasses for research on the human experience in outdoor urban environments. The objective is to investigate, through a series of experiments, how current mobile eye-tracking hardware and software can be utilized to provide a better understanding of how people experience urban environments; to develop an evaluation framework for the use of mobile eyetracking systems for research in human experience in urban environments and as an extension, how research techniques based on mobile eye-tracking can inform the design and development of urban spaces and services provided within them.

We use a mixed-methods approach to collect data by combining mobile eye-tracking, think-out loud protocol, observational studies, and interviews. Although ethnographic studies impose various constraints for this research, we explore using ethnographic studies as additional evaluation methods to increase the validity of eye-tracking data. What’s more, we provide a holistic framework of assessments that considers individual differences and needs of pedestrians for us to understand human experience in the urban environment better emotionally while empathetically.

Methods

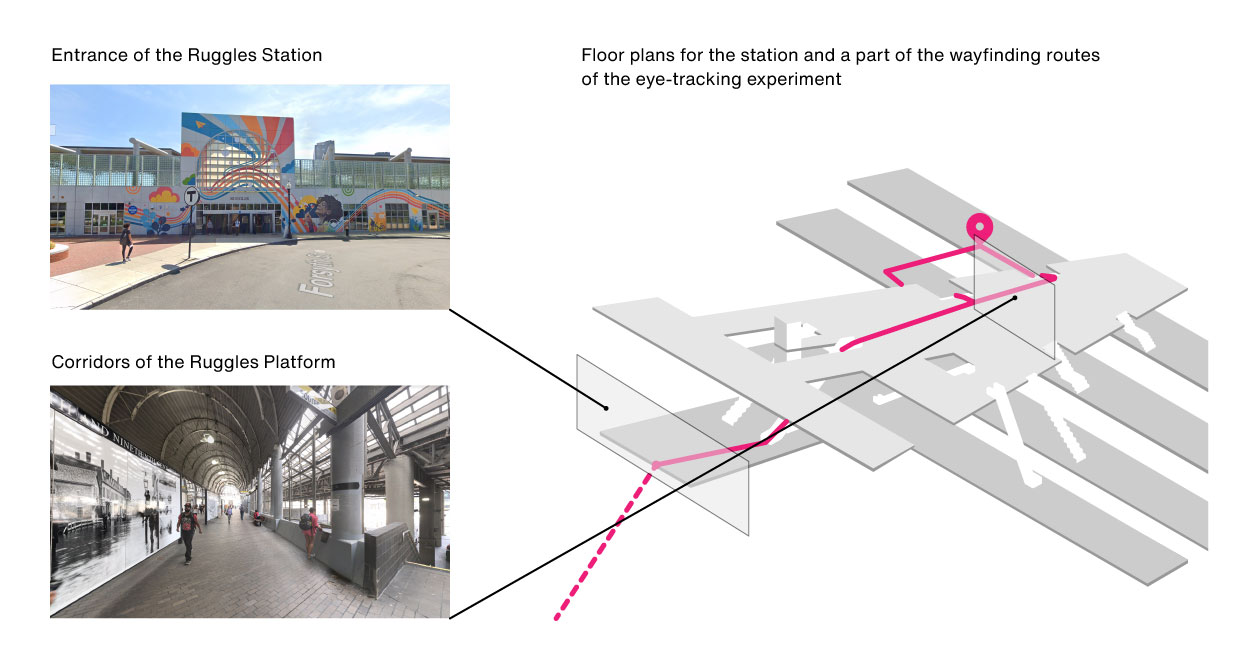

To drive the study in the urban context, we asked participants to do a wayfinding task when they were walking on the street. During the experiment, participants were wearing mobile eye-trackers while finishing an aided wayfinding task: find a specific bus stop located inside an MBTA station in Boston (the Ruggles station) (Figure 1). The wayfinding task narrows down the scope of research in understanding urban human experience in a specific behavioral setting. We categorized the participant’s environmental knowledge about the place into destination knowledge, route knowledge, and survey knowledge.

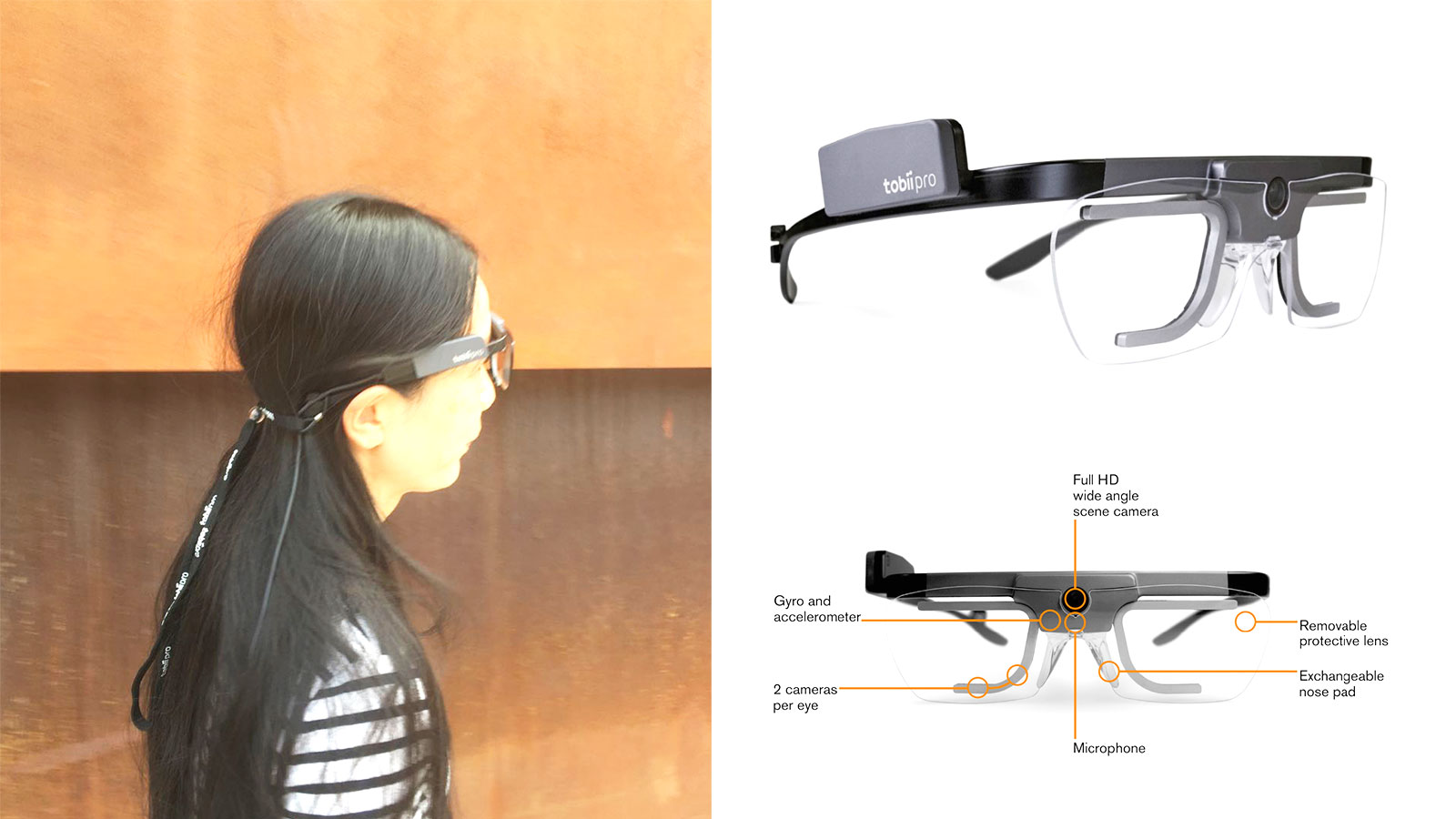

We use Tobii mobile eye-trackers Pro 2 to conduct the experiments with the iMotion software station to aggregate and prepare the raw data. All data analysis and plots were finished in python language with relevant libraries in data wrangling and visualizing.

Procedure and Data Processing

We incorporated three ethnographic research methods with eye-tracking studies in our wayfinding experiments, including observational studies, interviews, and think-out loud protocol. First, we asked participants to do a think-out loud protocol study when they were completing the wayfinding task on the street while wearing the mobile eye-tracker. Second, we conducted interviews after they complete the wayfinding task. This lets us understand their holistic feelings about the trips and find out certain environmental stimuli in which they find interested to remember. Third, we asked participants to do another round of think-out loud protocol when they were watching the tracing video. To be specific, participants answered what they are looking at and whether they still remembered those environmental elements.

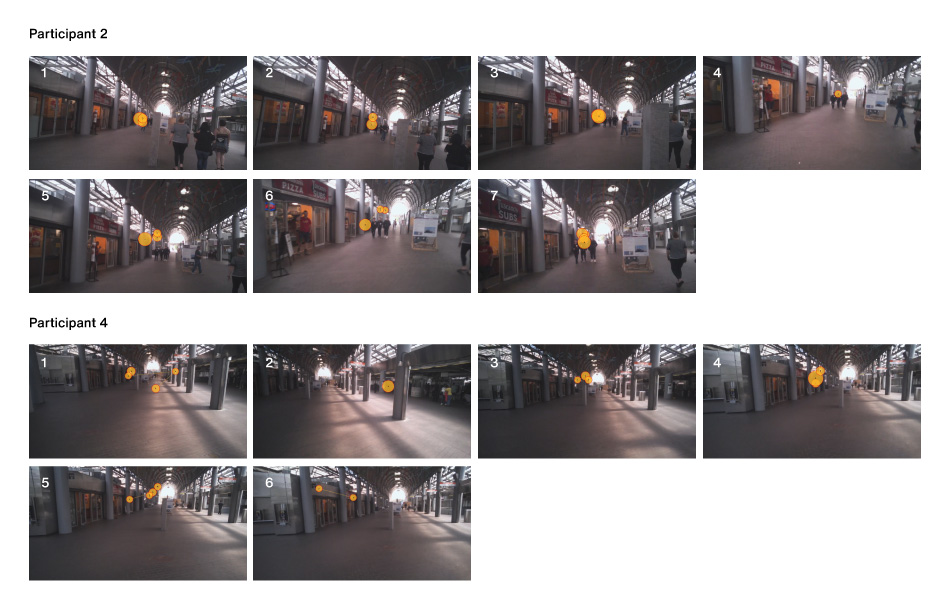

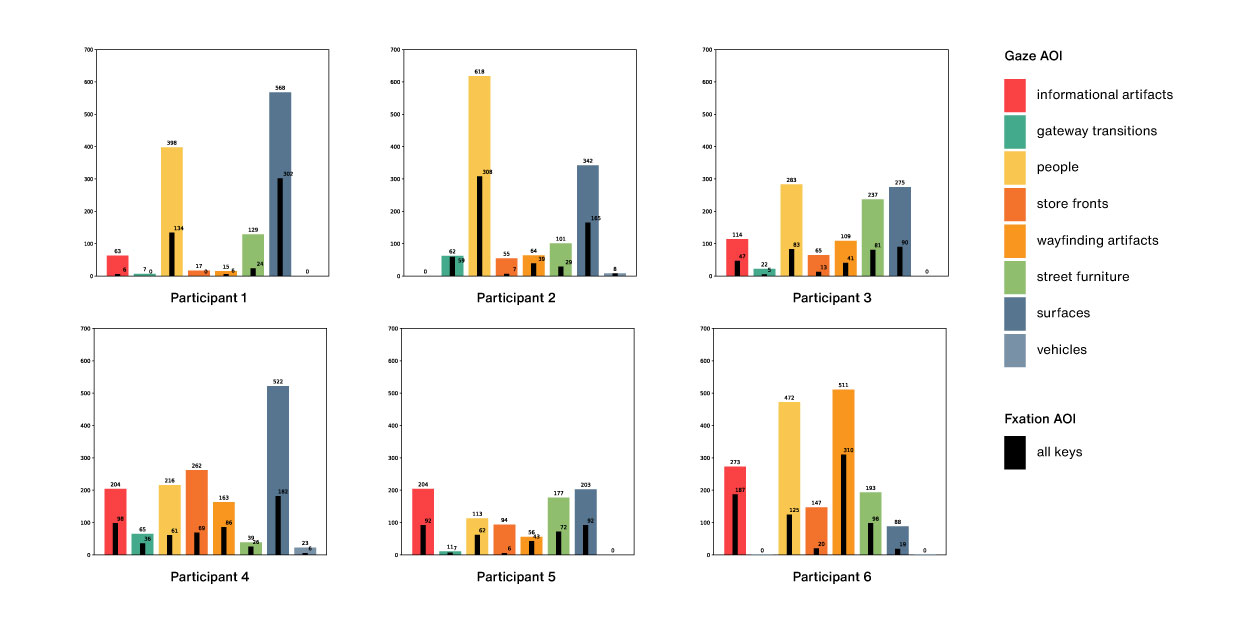

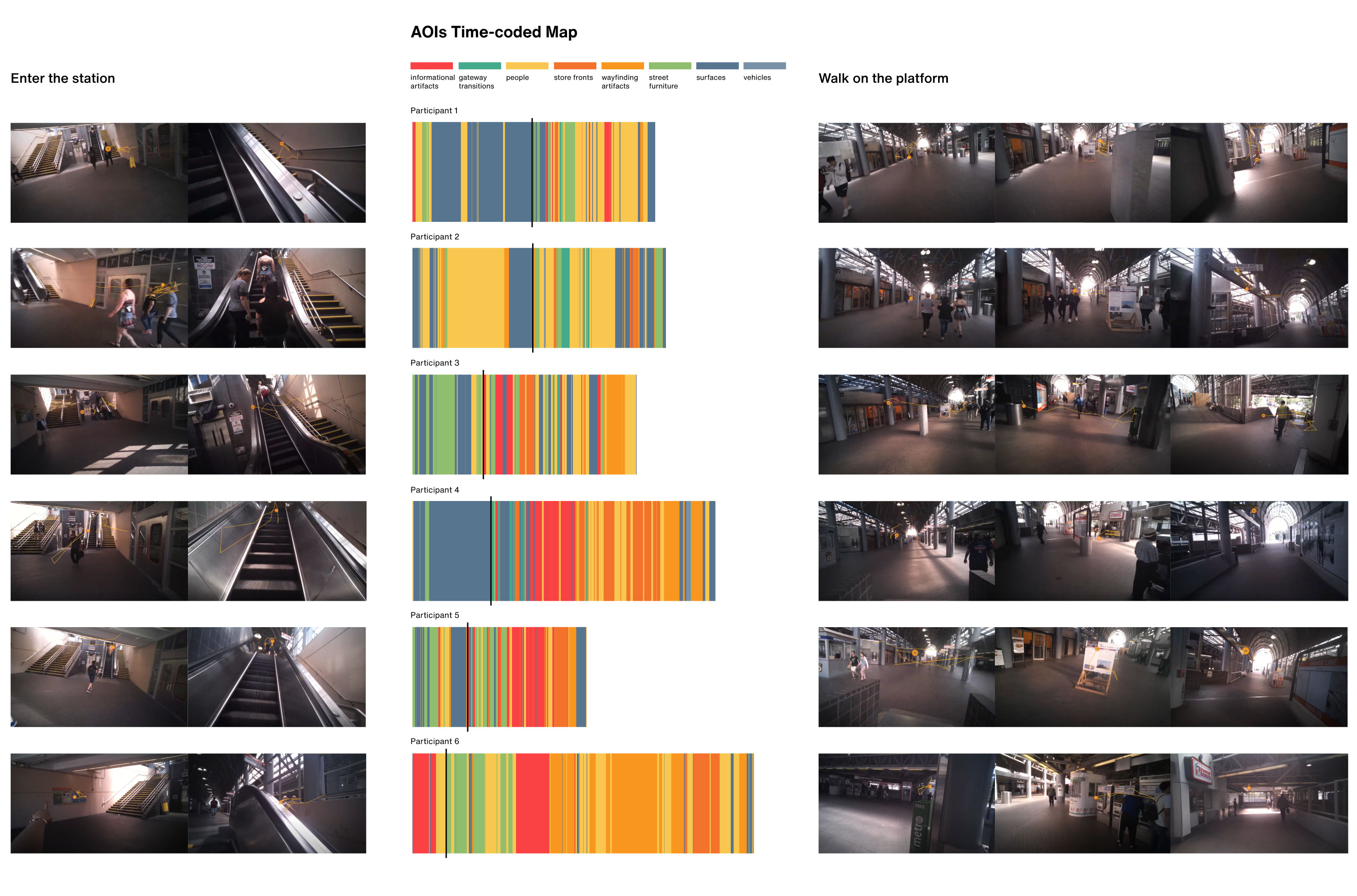

For the data processing, we calculated the AOI key of total gaze and fixations into a million seconds for each participant. By plotting the bar plot of the AOI key, we can have an overview of what participants usually see on the path and how their visual attentions distribute (Figure 3). As the fixation implies stronger human attention than the gaze, this allows us to identify what elements are more visually attractive to participants. To understand how the eye-tracking data is relevant to the context and task, we use an AOI map which concatenates the AOI (ms) into the time sequence (Figure 4). By comparing the real image of the environment, we assume that the AOI map of different participants might be useful to find visual patterns when people walk in a specific environment.

Insights

In this research, qualitative and quantitative data are mutually referred to each other when we analyze the key topics of the wayfinding trips and the difference between what they see and what they speak from different sources. We summarized the key topics from the qualitative data ranging from what participants usually see, what they usually do, how they feel about the place by comparing different participants’ results, and what unexpected behaviors and actions are shown by comparing the ethnographic account with the AOI results.

First insight: it is interesting but unsurprising to find that people are a strong environmental stimulus that attracts participants’ attention. Compared to lots of previous findings that urban edges are visually engaged and attracted for pedestrians, the quantitative data above also supports the results, but we find “people” is an interesting topic to explore.

Although it is private and sensitive for researchers to ask and understand why participants looked at people, “people” are usually the important urban elements that influence observers’ actions and behaviors. By looking at what other people do, observers adjust their own behaviors of navigating in the urban space. This strategy of situating themselves around places does not only depend on seeing people but also hearing the voice and noises from people of their social lives in the urban space.

Second insight: when reviewing the traced video, we found that participants were informed by visual cues to learn where to go. These visual cues are a combination of visual signals from the urban structure and directional information from wayfinding artifacts. They work together and imply pedestrians about the path to the destination. Although the directional information is limited at the beginning of the wayfinding tasks, by analyzing the perceived urban environment and reflecting their task-oriented goals, participants can identify the way to the road exit or the corner area as the possible direction to the destination.